The way forward from warehousing seniors to a more humane approach to senior care

Notes from the field | February 17, 2022

COVID-19 has proven to be a watershed event in the way we approach the design of long-term care (LTC) facilities. The pandemic has brought into sharp focus how a chronic practice of ‘warehousing’ seniors within large institutions can negatively impact the safety and well-being of its residents.

In this article, Mary Chernoff, Principal at In-House Design Services, discusses the cottage model of care as an alternative to this practice and a path forward to a more human-centered model of care.

"We've had a lot of time to see how this 'warehousing' treatment works and doesn't work. I love the neighborhood model, we pioneered this about a dozen years ago. The smaller care model brings so much to residents' lives, and to caregivers' lives too."

– Mary Chernoff

Q: How did the design and planning of many senior care homes contribute to the rapid spread of the virus during the COVID-19 pandemic?

For years, the LTC sector has been grappling with chronic underfunding and a growing population of seniors needing care. We simply have not invested enough to meet the needs of an aging population, and this is clear when we look at the physical set-up of our long-term care homes.

Much of our current LTC housing facilities are old and outdated, and they remain in service even after standards of care have changed. Many buildings still accommodate multiple people in bedrooms with shared bathrooms, which, as we have witnessed, becomes a major threat to controlling the spread of infection.

These facilities (and note, I call them facilities, not homes) tend to warehouse seniors in line with a traditional acute care approach in order to deliver maximal clinical services at minimal cost. They often share the same defining features—a hub and spoke approach where long, narrow corridors with resident rooms on either side fan out from a central nursing station, designed for efficiency for staff, not the dignity of residents.

Communal spaces like dining rooms and lounges are shared by the entire building’s residents. Often times eating in the dining room can feel like eating in a bus station. Staff are itinerant, working across multiple areas or in several care homes instead of being dedicated to one.

Combined, all these factors make infection prevention and control challenging, if not impossible—something we have been witness to this past year.

Q: As a designer, how do you address the tendency toward warehousing of seniors?

If we want to move toward a more humane and respectful senior care model, we need to reconsider how we’re designing senior care facilities. I really feel a smaller care model should be incorporated into all new senior care home builds.

Smaller care models, like the Green House Model, move away from the one-size-fits-all philosophy toward a “person-directed care” approach that emphasizes autonomy, dignity and well-being.

In this model instead of housing, say, 240 people in a big tower, you have individual neighborhoods or cottages, with about 12 people per unit. Each person has their own bedroom and bathroom, and the group shares a kitchen and a living area—there are no long hallways to the bedrooms. Staff are dedicated to each cottage, enabling a deeper level of connection between residents and caregivers.

Hamilton High Street Residence shared living room area. Photo: Jerald Walliser Photography.

Hamilton High Street Residence shared living room area. Photo: Jerald Walliser Photography.

Taking this approach supports a more intimate delivery of care. In fact, it models the feel of a home as residents become part of a ‘family unit’ with whom they can connect and dine with and ultimately take comfort from.

It also reduces the amount of human traffic (staff, family) passing through the space, consequently reducing risk of infection spread.

Proof positive—these smaller settings with fixed staff generally have had lower COVID-19 rates. Why? Because we were able to bubble these units, hunker down and keep our seniors safe, while still enabling them to enjoy having the company of their house-mates, unlike the larger care approach where residents have basically been put in isolation within their rooms with zero interaction with others. That is not humane!

Q: Are there ways to implement this cottage model of care and still realize some cost efficiencies?

Well, let me clarify—small care models don’t have to refer to just the overall size of a building. It’s partially that, but it’s also about delivery. You can have a 200-person home, but it can be broken down into smaller areas or household

bubbles.

For example, a recent project I worked on called Whistle Bend Place will eventually accommodate 300 beds when phase two is complete.

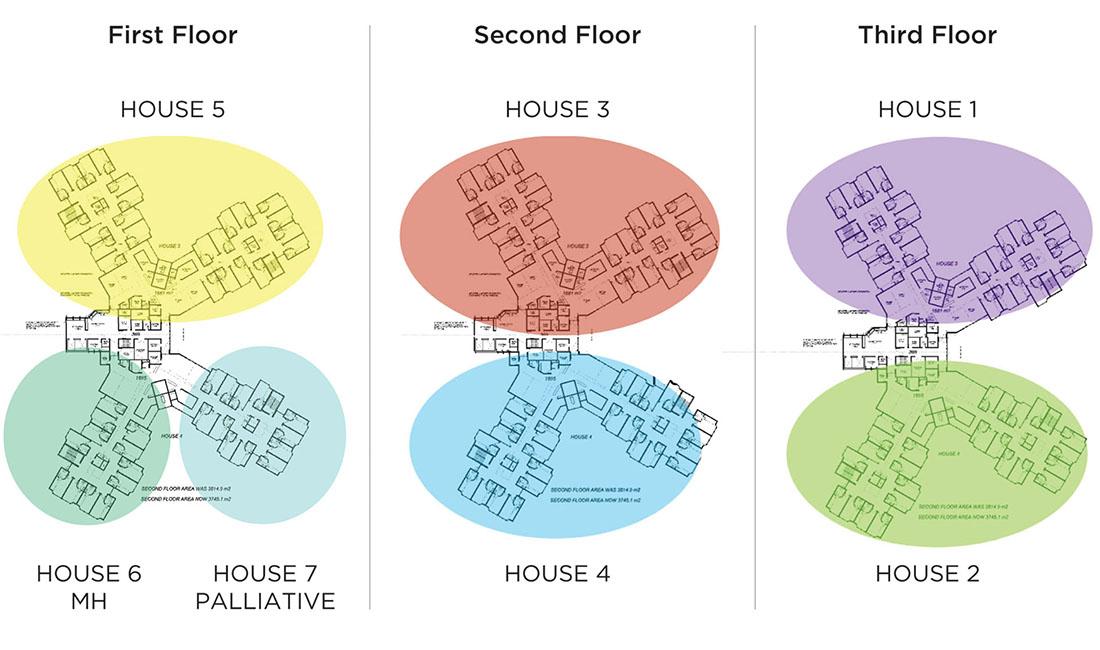

A neighborhood approach groups residents into smaller, more intimate living quarters. Shown here is the plan for Whistle Bend Place.

A neighborhood approach groups residents into smaller, more intimate living quarters. Shown here is the plan for Whistle Bend Place.

The building design groups residents into discrete households, each having their own front door that opens into family areas, activity spaces, kitchen, dining rooms and private resident suites. All neighborhoods are then connected to a “village center” containing features and services that are shared by all, including shops, services, day programs, multi-use rooms, a kitchen, laundry, storage, and staff and administrative spaces.

Grouping neighborhoods with shared amenities not only allows for operational and cost efficiencies, but also for more meaningful features to be incorporated into the facility—things that can keep residents connected with their culture and community for a better quality of life.

In Whistle Bend Place, that included a healing room informed by Yukon First Nations’ culture. We need to determine what is appropriate for the resident community and design to their specific tastes, not duplicate the same building and floorplan everywhere.

Neighborhoods at Whistle Bend Place contain their own kitchen, dining and lounge areas, enabling residents to create deeper bonds.

Neighborhoods at Whistle Bend Place contain their own kitchen, dining and lounge areas, enabling residents to create deeper bonds.

Grouping shared services such as a salon in the village centre provides cost efficiencies and opportunities to socialize.

The incorporation of a healing room at Whistle Bend Place ensures residents' culture is respected and that they remain connected to their community and beliefs.

The incorporation of a healing room at Whistle Bend Place ensures residents' culture is respected and that they remain connected to their community and beliefs.

Q: What’s next—what is your hope for the future of senior care?

Looking forward, my pipe dream for before I retire is to see the smaller care model integrated within the community—like what they are doing in the Netherland (Humanitas) where free housing is offered for students and young people within the residence in exchange for time spent with their senior neighbors.

I want to see seniors remain part of the community—not be shut off as “other”.

There are glimpses of this happening across the country. At the Sherbrooke Community Center, they integrate a daycare immediately adjacent to the facility. They also have a grade six school class as part of iGen, an intergenerational classroom program designed to provide close and continuing contact between elders in long-term care and school-aged children. Students have class in the basement in the morning. In the afternoon they visit and do activities with the residents.

While the building is quite ordinary, it is the passion and the desire to make it a better place by integrating its residents with the surrounding community that really makes it special. That is my hope for a better future for senior care.

"This crisis or this pandemic has proven to us we are doing the right thing [moving toward a new model of care]. For me, it's not all doom and gloom. It's positive—and I'm optimistic about [it]."

– Mary Chernoff

![]()

Mary Chernoff, RID EDAC

Interior Designer

Principal, In-House Design Services Ltd.

Mary has specialized in healthcare design for the last 30 years, balancing acute care hospital projects with the spectrum of independent living, assisted living, complex care and dementia care facilities design.

She has witnessed and participated in the great change and improvement in elder care facilities over the last few decades and designed one of the first cottage models in British Columbia (Hawthorne Dementia Care Cottages, 15 years ago). She is equally proud of a few of her other long-term care projects: The Residences at Clayton Heights, a 139 bed residential care facility in Cloverdale, BC, and the 150 bed Whistle Bend Care Facility in Whitehorse, YK.

She has consulted on numerous P3 and design-build projects from both the design team side and the client/compliance side. She is well versed in facilitating the user consultation process and takes an avid interest in weaving together the various streams of signage, art, furniture and donor recognition that bring a large project to a cohesive completion.

Mary is currently leading the design for Royal Columbian Hospital’s Phase 2 Redevelopment, in her hometown of New Westminster, and also a new 125 bed care facility, Guru Nanak Diversity Village, for PICS—the Progressive Intercultural Community Services Society in Surrey. She has just completed Royal Inland Hospital’s Patient Care Tower in Kamloops and Riverview’s Centre for Mental Health and Addiction in Coquitlam, along with the Hamilton High Street Residence—a Seniors Living Campus—in Richmond, BC.

Enjoy this article? Don't forget to share.